The poem I’m sharing today, I wrote several years ago. I don’t think it’s my best work, but it was one of the first poems that I took a very structured approach to, and in some sense planned out before I wrote it. It was also the product of several circumstance that unfolded over several months, so I’ll share the poem here first, and then give the story behind it’s creation. As I’ve been growing my publication here, I’ve found one of my aims is not only to share poetry, but to give some insight into it’s construction, to look under the hood, so to speak. Not only does this give you, as a reader of poetry, a deeper appreciation, but hopefully it will inspire you to try your hand at verse. In a better time and a more vibrant culture, the ability to commit your thoughts to verse and thereby elevate both your words and your thoughts, should be far more common. So, with the only example I have, myself, I hope to give you some insight into how a poem may grow from a quiet thought, and through time and toil, eventually come to life on the page.

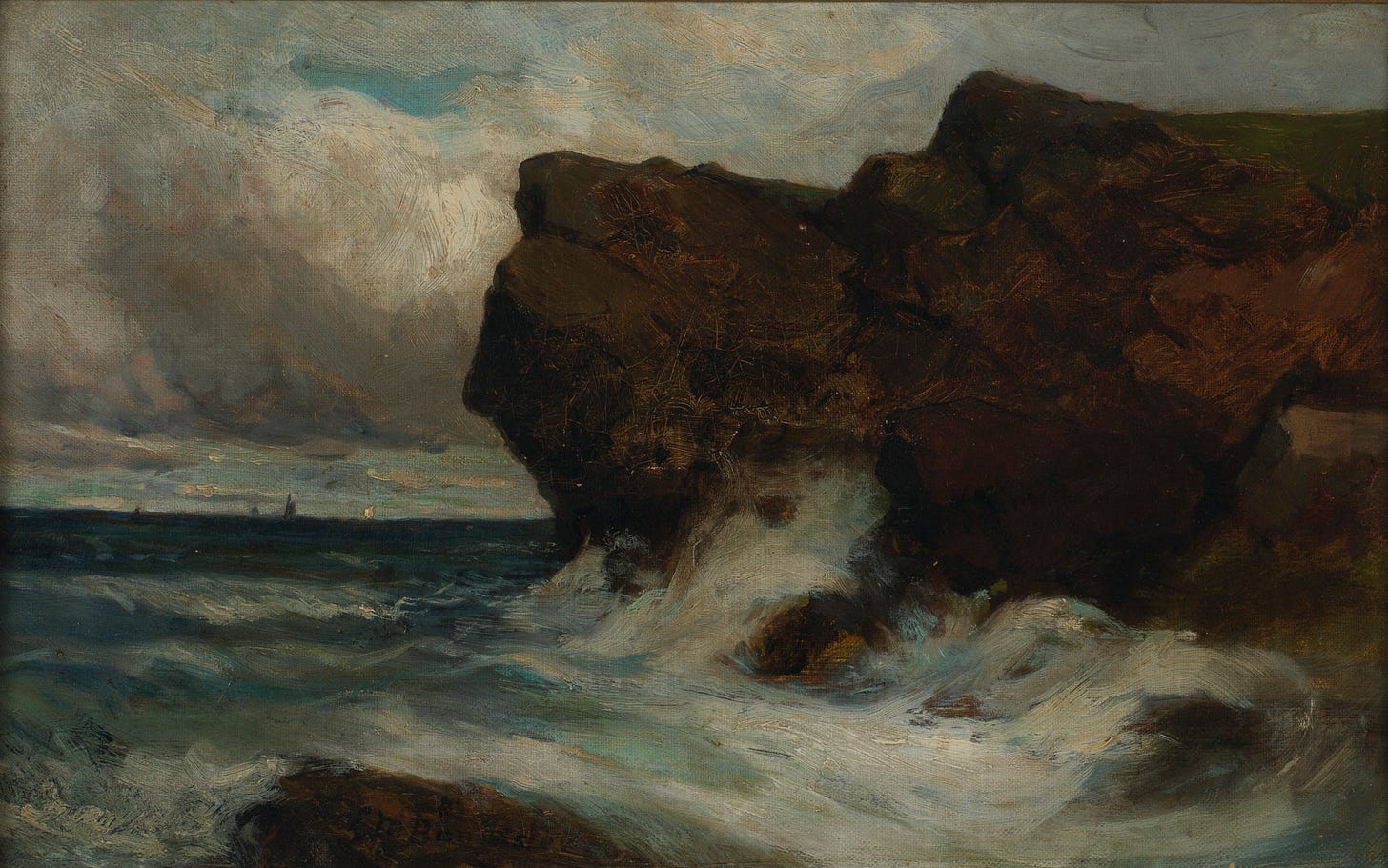

Ocean Cliffs (Edward Michael Bannister, 1881)

The Stony Cliff

Beneath the stony cliff the maiden knelt Along the pebbled shore, And wept for him who took her heart, and sailed Away the day before. Both salty tears and salty spray Were mingled in her eyes that day, And every day, till days she had no more. Along the stony cliff the friar walked While deep in lofty thought, Of how eternal life and death are long, And life of man is short; How as the vastness of the sea, So shall our Father’s mercy be, To such as who, His holy will, have sought. Atop the stony cliff the sovereign stood, Surveying sea and land. The earth beneath his feet a stately throne, The waves at his command. Where endless ocean meets the sky, So far did his ambitions lie, The reaches of the world within his hand. Down from the stony cliff the poet gazed Through mists of troubled heart. The light of life which once he oft beheld, No light could now impart. The raucous cry of foam on shoal Demanded his immortal soul, Should, with the deep’s receding tide, depart. Beside the stony cliff the pilgrim passed, His weary way to wend. So far he’d come from whence he had begun, Yet far from journeys end. For every wave that lapped the shore, Of steps he had a thousand more; For every step, another sin amend. From this, until the close of time and tide, The stony cliff remains; A witness to the victories of men, Observer to their pains. And as I look me out to sea, The wind and waves recount to me The stories that this precipice contains.

Coffee on an Island

The story of this poem’s life began, as you might suspect, on a cliff overlooking the sea. It was late January 2021, and I was on Stradbroke Island off the coast of Brisbane, Australia, in the middle of a Queensland summer. I had gone for a walk early that morning to get a coffee, and afterwards made my way towards the lookout just up the road. Once I arrived, rather than stopping at the fence meant to keep adventurous holiday-makers at bay, I climbed over and scrambled down the cliffside to find a spot to sit. I wanted to get as close to the ocean as possible. Once I found a place where you could see practically nothing but sea and sky, I sat there in silence and tried to drink in that powerful effect that we’re all familiar with when you stare at the endless expanse of water reaching to the horizon, and beyond to unknown shores.

Then that thought struck me, that this is an experience that we’re all familiar with. That the ocean and it’s power is undeniable, universal, has been a source of inspiration for men throughout the centuries. In fact, someone else may have sat in the very place I’m sitting a hundred years before, and someone else may sit a hundred years hence.

I then began to think about these people, their stories. Depending on the state of one’s mind or soul, the moment when you stand between the intersection of sea and land would speak very differently. For one, the calm tranquillity of a still ocean sunrise would inspire peace. For another, the relentless power of the ocean eroding the land in an eternal war of attrition might inspire fear and intimidation.

A host of different characters and metaphors passed through my mind. I knew there was a poem here somewhere.

I sat, finished my coffee, then went to a get an ice cream and go for a swim. I didn’t think about it again that day, or for several months.

But the seed had been planted.

Sea Breaking on Stony Cliffs at Left (James Ward)

Vespers on a Bigger Island

Several months later, in May 2021, I was on a different, much larger island over 2500 kms away from where I’d sat that morning and drank my coffee. I had come to the Benedictine foundation of Notre Dame Priory in Colebrook, Tasmania for a two week working retreat, to help build some new cabins. Being a carpenter by trade, I was able to help the monks, who came from a variety of backgrounds, complete the cabins in time for the impending Tasmanian winter. We all got along tremendously well together, and the work progressed quickly.

Every evening, after hanging up the toolbelt, I would walk down to the chapel to sing vespers with the monks. The Tasmanian sunset would throw rich purples and oranges onto the sky, and cast into silhouette the lone homesteads that spotted the countryside, while the distant sound of lambs filled the air, and the cold wind of winter’s anticipation stung your face. It was a magical scene, and worthy of a poem itself.

One particular evening as I sat in the chapel, one of the images that had crossed my mind that day on the cliff, entered my imagination with an accompanying line:

“Atop the rocky crag, the Scotsman stood/

and looked him out to sea.”

It was a simple image, but I couldn’t get the metre out of my head.

One line of five iambs. One line of three.

(For those who may not remember, an iamb is a “foot” of two syllables, with the second syllable stressed. I’ve put the stressed syllables in bold above to help see the metre.)

If you put them both together, they make eight iambs which you would usually divide evenly into two sets of four,

“Atop the rocky crag, the Scots/man stood and looked him out to sea.”

But the division of five and three created an interesting rhythm, and the opportunity to have a long idea followed by a short idea that completed it. I must admit, I didn’t pray as well as I should have that night, because my attention was completely consumed by how I could make this metre work, and the original train of thought that I had embarked upon all those months ago was taken up again. I rushed back to the priory guest house once vespers was completed and pulled out my notebook.

Cliffs and Conquerors

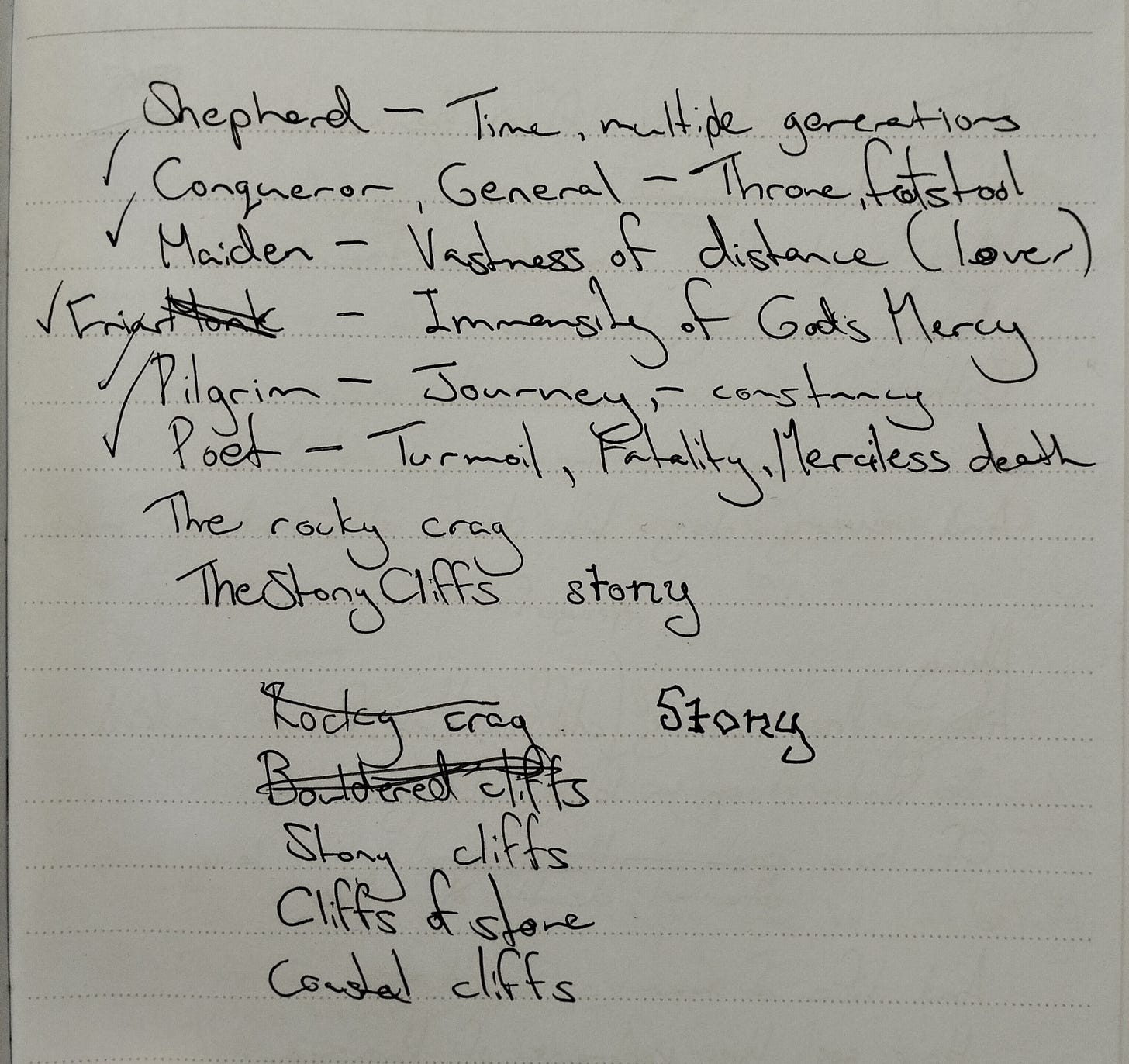

Because I was starting with a very specific metre, I knew I had to apply the same degree of structure to the whole poem. The idea of the variety of metaphors that the ocean could inspire resulted in a list.

In one column a particular element of the sea’s power as the object of inspiration, in the other, a character who would be the subject.

The original page in my notebook.

With ideas like vastness, constancy, fatality, God’s mercy, I came up with a series of characters: The Maiden, the Friar, the Conqueror, the Poet, the Pilgrim. (I never got around to completing a verse for the Shepherd, he eluded inspiration somehow. The original Scotsman never made the team either.)

Now that I had characters to inhabit my poem, I needed to finalise the metre. I wanted to contrast the five against three rhythm with the typical four so I came up with this structure in the end.

Five

Three

Five

Three

Four

Four

Five

Having the two lines of four in the middle meant I could use that space to keep a particular idea, so I decided that those two lines would contain the specific reference to the ocean that I was trying to connect to the character.

Both salty tears and salty spray Were mingled in her eyes that day,

How as the vastness of the sea, So shall our Father’s mercy be,

Where endless ocean meets the sky, So far did his ambitions lie,

The raucous cry of foam on shoal Demanded his immortal soul,

For every wave that lapped the shore, Of steps he had a thousand more

You can taste the saltiness, along with the bitterness of the maiden’s tears, sense the vastness of the ocean of God’s mercy in which our sins are lost as a single drop of water. The endlessness of man’s hubris, and then the darkness of the sea’s fatal power, that is at once a terror and relief to the despairing soul.

The final element that brought the entire poem together, was a silent character that had not been a part of my initial process. Quite apart from any sense of the sea and it’s force to impress the various characters that passed by, the common thread between all the verses, was the cliff itself. Then came the idea that amid the turmoil of the lives of men, and the rise and fall of civilisations, amid the storms that lash the coast and of nation’s as they storm across history’s page, the cliff is the silent, unchanging, unmoved witness to it all.

And so over the next two nights, I wrestled with pen and notebook to bring all these elements together. And now I bring them to you in completed form. I hope you enjoy it.

If I can offer any final advice, find your own ocean cliff, or a forest, or an empty field or a night sky. Then find silence, and try to hear what human ears cannot hear, and see what human eyes cannot see.

Then days, maybe weeks or months later, find a pen and paper, and try to find the words.

Or perhaps wait for the words to find you.

Thomas McKendry

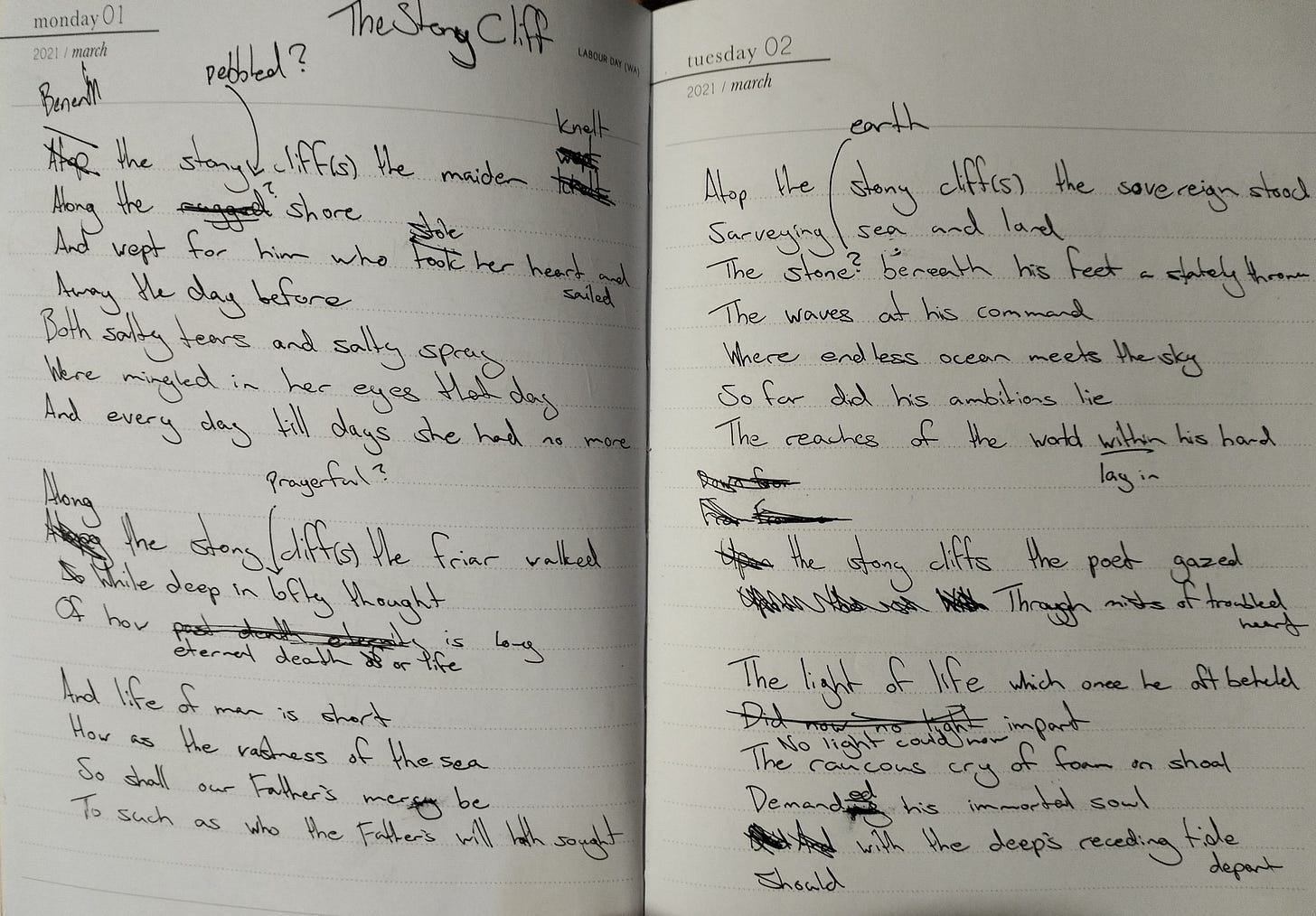

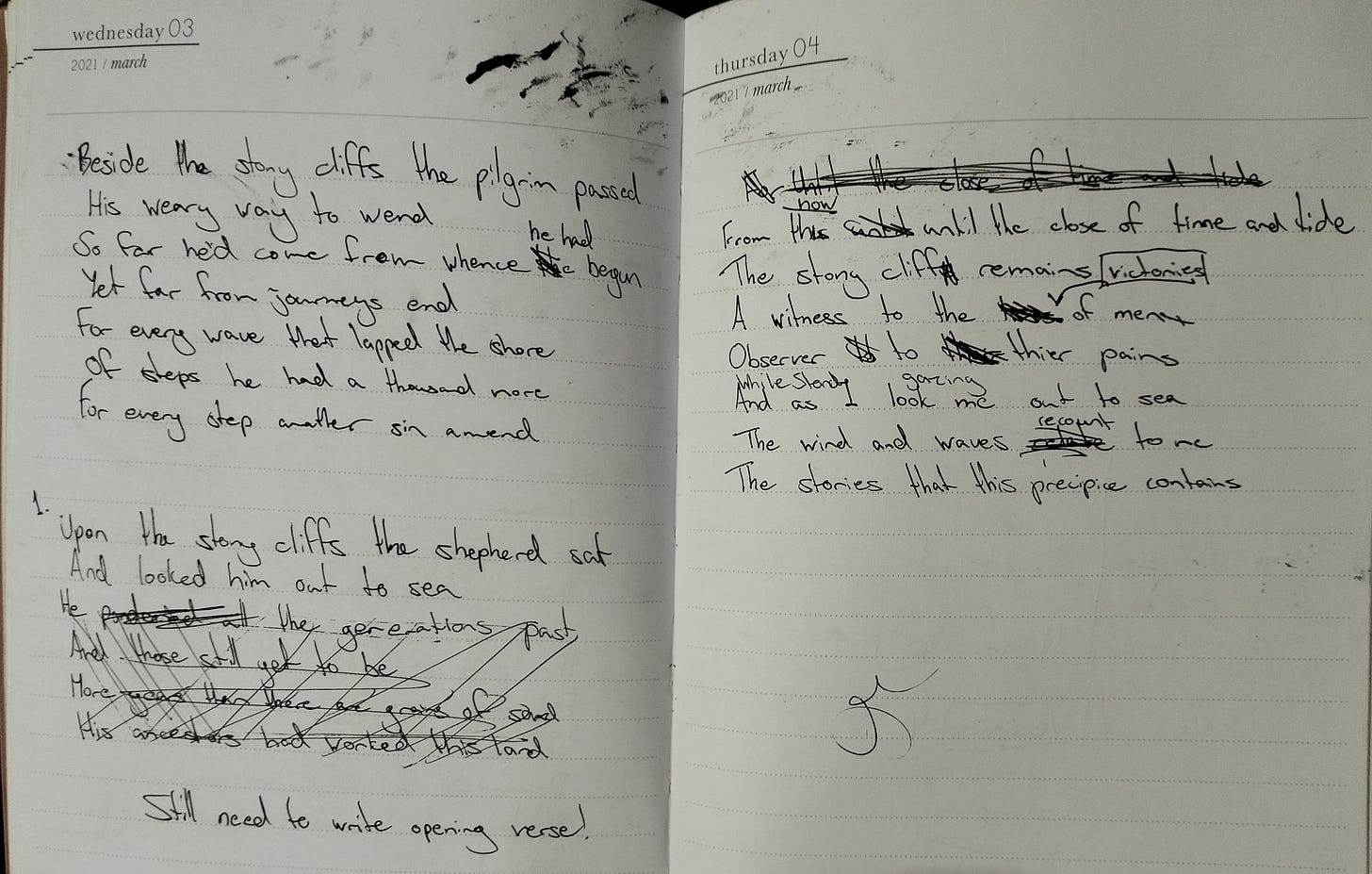

More messy notebook pages. A poem never starts its life in perfection, but in scribbles and ink stains.

Your notes look like mine...

and some of the way you seem to work out the syllables etc very much my way... but do yourself a big favor: do not let your half-finished work and your ideas on scraps and in notebooks get out of hand...l am just turned 71 and am only now able to work on sorting through my numerous journals and too many scraps to find if anything's worth editing let alone publishing on here. I wish you God's graces on your life's journey through writing and carpentry work and monastic and other good works!

You are a kindred spirit